It seems to be the way of things…. As the sun hits the lowest point in the sky, closely followed by Christmas and the accompanying ‘bedding down', we instinctively take stock of our belongings. We prune, consolidate and reacquaint ourselves with them. This usually means a trip to the dreaded loft; often the by-product of looking for dishevelled Christmas decorations in amongst the cobwebs. This is what I did not more than a few days ago, only to discover a leak brought on by a missing slate in the roof and some resultant damage to some of my stored possessions. As always seems to be the case, fate cruelly decided that the damage was done specifically to those items that mean most and cause the biggest heartache and regret. A punishment handed down by the ‘fairies of guilt’ for not being more conscientious in protecting the items placed in my care.

This time it was a poorly packed box of sheet music. As I say, I only have myself to blame, but this only sharpens the blow. Sheet music is a funny one for a musician. To me I suspect it holds a greater gravitas than even a photo would for a non musician. As is so often the case, (and as Joni Mitchell so accurately suggests) ‘don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you got till it’s gone’. This was brought home to me as I picked my way through the sodden and mouldy remnants of one part of my sheet music collection. Victims of this domestic flood were many music compendiums that were part of my musical education as a child and, even worse for my conscience, the only existing copies of some original sheet music that my father wrote many decades ago. Oh the culpability, oh the agony.

This sad discovery corresponds to an area I have researched deeply for the making of ‘Battery Life’ (via my mothers diaries and other source material)... a study of what constitutes a memory and its value. This was most exquisitely illustrated to me recently by the 2018 Finnish film ‘Flame’ by Sami van Ingen. A short film consisting of the last remnants from the only surviving reels of the 1937 film Silje, which were burnt in a 1959 studio fire. The beauty of the fire damaged film stock, presented in slow motion, vastly outweighs anything that one could have gleaned from the original. It is a sense of loss and poignancy, our vulnerability to the passage of time and natures course. How one artistic endeavour can completely transform its meaning through degradation and destruction. The actresses face that shoots a glance at you from amongst the bubbling, fire damaged film stock pierces your heart in a way that the perfect original never could. It is the drama within the drama of a body of work that required so much effort and dedication to produce at the time, utterly destroyed in a way that its creators could never have foreseen. The last echoes of a piece of art gone for ever, lost and never to return.

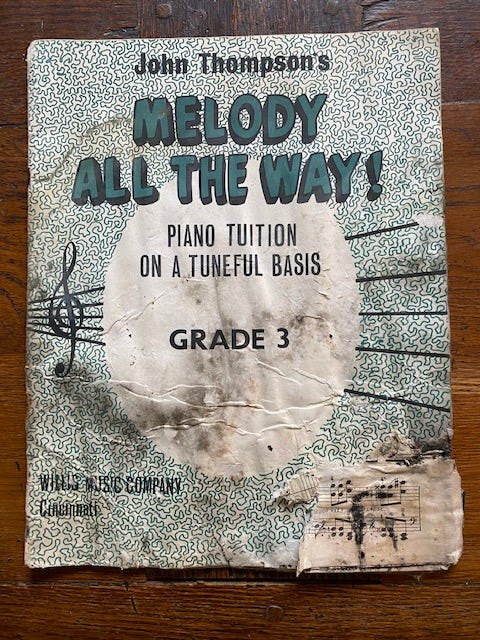

Back in the loft, one of the first pieces I picked up was one of those early piano tutor books that one buys in the first years of learning an instrument. A publication called ‘Melody All The Way’, which gave me as a young pupil a short tune every week to learn and perfect. As I peeled through its water damaged pages in my loft, I could see parts of illustrations that were inedibly printed on my brain. Little cue cards to revive memories of sitting upon the piano stool with my teacher Mrs Rixon at my side, gifting me the first fundamentals of becoming a piano player. A ritual that was repeated every Saturday morning, after a bumpy journey on the back of my mothers bicycle. My mother paid £1 per week for these crucial early lessons. A rate that, even in her single parent circumstances, she could afford. It seems my childhood was littered with people providing their time and instruction way beyond the value at which they asked to be remunerated. A gift to blossom through the generations.

As well as water damaged music and illustrations on this wet voyage of discovery I was able to see actual pencil notes from the aforementioned Mrs Rixon, giving me a date on which each piece was undertaken (in this case 1978 onwards) and explanatory notes and performance suggestions. Just the mere sight of those scrawled instructions still give me a sense of being under the wing of someone most assuredly in charge.

The most powerful element though is the music itself. To a piano player, the notes placed so deliberately on staves demand that you stride straight up to the piano and play them. You can already hear them in your head on first viewing, and you are compelled to manifest them on the piano keyboard. Not only do they sound out notes that you have not heard for decades, but they ‘feel’ familiar. They unlock a muscle memory locked deep away. This is an emotional and powerful feeling.

The missing, water damaged parts contain the same beauty I spoke of earlier in the fire damaged film. In some cases I can almost play out those now missing parts, having unlocked the dormant muscle memories. Not with complete conviction, but the shadows of these memories are there within me. You enter into a world of memory, reliant on whatever foundations one laid down all those years ago.

I am now committed to keeping these ugly, crumpled, disintegrating parchments, black with mould, for the poignant exercises in memory that they now are.

As for my fathers original sheet music; I can barely look at them for the guilt I feel in allowing them to be damaged. He was a professional musician and wrote a few minor hits 'back in the day’, (most notably a comedy record by the famous British entertainer Bruce Forsyth entitled ‘My Little Budgie’) but continued to compose later on in life perhaps in the hope of repeating these successes. One or two of them were dedicated to my mother and I remember them being played on my piano at home during his visits. I can’t bring myself to assess the true state that they are in just yet. They are currently hanging out to dry next to a radiator at the back of the house. They are probably the only copies ever to exist and were probably never recorded. Through my carelessness I may have allowed one or two valuable memories to pass into the 'lost domains’ irrevocably. This is hard to bear. Sure, I didn’t physically rain on them myself, but I could have stored them in something akin to a temperature controlled vault forty feet underground!…. Or something equivalent to their preciousness.

It’s definitely true to say that music has a deep meaning for me as it does for so many people. I have always known it to be more intrinsically linked to my being than the more visual cues in life and this is yet another example of its physical connection and power over me. I get more from a piece of sheet music than I do from a photo. It lifts me up out of my chair, it speaks to my muscle memory, it conjures up a recollection, it produces a feeling. I would venture to suggest that to a musician who is able to read notation, sheet music is the most interactive ‘photo album’ currently available. All the more powerful because it has a physical element that moves you both literally and emotionally. We all have our cues. These are mine and it’s good to remember sometimes. Even if, as is the case here, it comes at a high price!

Fingers crossed that your father's work is retrievable, Neil. I certainly hope so.

I confess that I've yet to hear Battery Life, but that's something I plan to remedy shortly. In the manner of the Silje/Flame movie you might do some works from your remembered music with improvisations in the gaps. An interesting exercise if nothing more.

My own experience with sheet music as a guitar player came through trying to self-train my ear into chord changes with charts from the hits of the late-'60s/early '70s - I briefly worked for a publisher at the time. They were inaccurate far more often than not. A few years later I realised most had been transposed into more piano-friendly keys from the originals.

The liberty!

This - https://youtu.be/wYw1Q3LFiNw?t=490 - presumably NOT on the list of lost / rain-damaged sheet music :-) And, thanks, that's a lovely article.